Part 2 of the SOLID Principles for Scientific Programmers series

The Validation Nightmare

You’ve spent six months developing and validating a data analysis pipeline for your research. Your advisor signed off on the methodology. You’ve compared results with published benchmarks. The code works perfectly, and you’ve already published one paper using it.

Then you need to add a new fitting algorithm to compare with your current approach. You open the code, find the analysis section, and add an elif statement. Simple enough, right?

But now you have to re-validate everything. Did your change accidentally affect the existing algorithm? Did you introduce a subtle bug in the control flow? Your advisor insists you re-run all the validation tests before you can use the code again for publication.

You just wanted to add a feature, not risk breaking what already works.

This is the problem the Open/Closed Principle (OCP) solves.

What Is the Open/Closed Principle?

Bertrand Meyer originally stated it as:

Software entities should be open for extension, but closed for modification. 1

In practical terms: You should be able to add new features (open for extension) without changing existing, tested, working code (closed for modification).

Think of it like adding a new instrument to your lab. You don’t rewire the entire electrical system—you plug it into an existing outlet. The infrastructure is designed to accommodate new equipment without modification.

Before You Refactor: Is It Worth It?

OCP requires upfront design work. Before refactoring, consider:

- How often do you add new fitting methods? If rarely, a simple if-elif is fine

- Is the code validated and published? OCP protects published results

- Do multiple people work on it? Multiple contributors benefit most from OCP

- Would breaking existing methods be catastrophic? High stakes justify the structure

If you answered “yes” to 2+ questions, OCP is worth implementing.

A Real Example: The Problem

Let’s look at a typical data fitting pipeline. This is the kind of code that grows organically as research progresses:

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit

from scipy.stats import linregress

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

class DataFitter:

"""Fits various models to experimental data."""

def __init__(self, x_data, y_data):

self.x_data = np.array(x_data)

self.y_data = np.array(y_data)

self.fit_result = None

self.method = None

def fit(self, method='linear'):

"""Fit data using specified method."""

self.method = method

if method == 'linear':

# Simple linear regression

slope, intercept, r_value, p_value, std_err = linregress(

self.x_data, self.y_data

)

self.fit_result = {

'params': [intercept, slope],

'r_squared': r_value**2,

'method': 'linear'

}

elif method == 'quadratic':

# Quadratic polynomial fit

params = np.polyfit(self.x_data, self.y_data, 2)

predictions = np.polyval(params, self.x_data)

ss_res = np.sum((self.y_data - predictions)**2)

ss_tot = np.sum((self.y_data - np.mean(self.y_data))**2)

r_squared = 1 - (ss_res / ss_tot)

self.fit_result = {

'params': params,

'r_squared': r_squared,

'method': 'quadratic'

}

elif method == 'exponential':

# Exponential fit: y = a * exp(b * x)

def exp_func(x, a, b):

return a * np.exp(b * x)

params, _ = curve_fit(exp_func, self.x_data, self.y_data)

predictions = exp_func(self.x_data, *params)

ss_res = np.sum((self.y_data - predictions)**2)

ss_tot = np.sum((self.y_data - np.mean(self.y_data))**2)

r_squared = 1 - (ss_res / ss_tot)

self.fit_result = {

'params': params,

'r_squared': r_squared,

'method': 'exponential'

}

elif method == 'power':

# Power law fit: y = a * x^b

# Use log-log transformation

log_x = np.log(self.x_data)

log_y = np.log(self.y_data)

slope, intercept, r_value, _, _ = linregress(log_x, log_y)

a = np.exp(intercept)

b = slope

self.fit_result = {

'params': [a, b],

'r_squared': r_value**2,

'method': 'power'

}

elif method == 'ridge':

# Ridge regression for regularization

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

poly = PolynomialFeatures(degree=3)

X_poly = poly.fit_transform(self.x_data.reshape(-1, 1))

ridge = Ridge(alpha=1.0)

ridge.fit(X_poly, self.y_data)

predictions = ridge.predict(X_poly)

ss_res = np.sum((self.y_data - predictions)**2)

ss_tot = np.sum((self.y_data - np.mean(self.y_data))**2)

r_squared = 1 - (ss_res / ss_tot)

self.fit_result = {

'params': ridge.coef_,

'r_squared': r_squared,

'method': 'ridge'

}

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unknown method: {method}")

return self.fit_result

def predict(self, x_new):

"""Make predictions using the fitted model."""

if self.fit_result is None:

raise ValueError("Must fit model first")

x_new = np.array(x_new)

# More if-elif chains for prediction

if self.method == 'linear':

intercept, slope = self.fit_result['params']

return intercept + slope * x_new

elif self.method == 'quadratic':

return np.polyval(self.fit_result['params'], x_new)

elif self.method == 'exponential':

a, b = self.fit_result['params']

return a * np.exp(b * x_new)

elif self.method == 'power':

a, b = self.fit_result['params']

return a * x_new**b

elif self.method == 'ridge':

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

poly = PolynomialFeatures(degree=3)

X_poly = poly.fit_transform(x_new.reshape(-1, 1))

# Wait, we don't have the ridge object anymore!

raise NotImplementedError("Ridge prediction not available after fitting")

raise ValueError(f"Unknown method: {self.method}")

def get_residuals(self):

"""Calculate fit residuals."""

predictions = self.predict(self.x_data)

return self.y_data - predictions

def plot(self, title=None):

"""Plot the original data and fitted curve."""

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create a dense x range for smooth curve

x_smooth = np.linspace(self.x_data.min(), self.x_data.max(), 100)

y_smooth = self.predict(x_smooth)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.scatter(self.x_data, self.y_data, label='Data', s=50, alpha=0.7)

plt.plot(x_smooth, y_smooth, 'r-', label=f'{self.method.capitalize()} fit', linewidth=2)

plt.xlabel('X')

plt.ylabel('Y')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.title(title or f'{self.method.capitalize()} Fit (R² = {self.fit_result["r_squared"]:.3f})')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

def compare_methods(self, methods):

"""Compare R² values across multiple fitting methods."""

results = {}

for method in methods:

try:

fit_result = self.fit(method)

results[method] = fit_result['r_squared']

except Exception as e:

print(f"Warning: Method '{method}' failed: {e}")

results[method] = None

return results

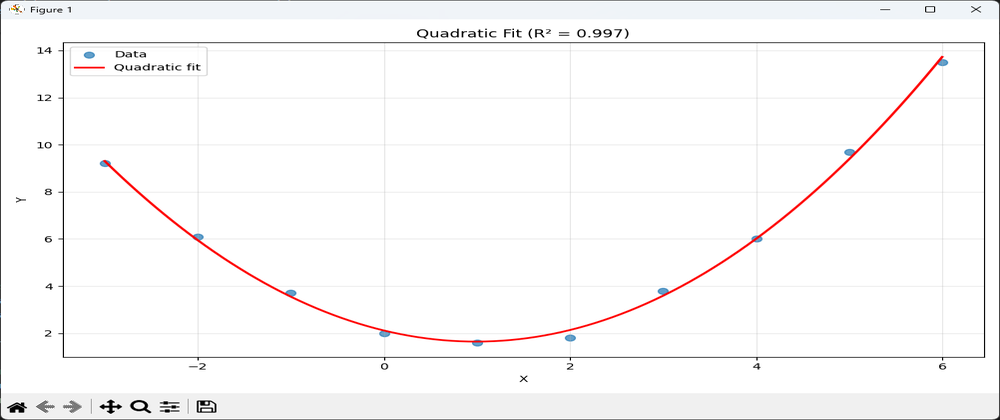

# Usage

x_data = np.array([-3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6])

y_data = np.array([9.2, 6.1, 3.7, 2.0, 1.6, 1.8, 3.8, 6.0, 9.7, 13.5])

fitter = DataFitter(x_data, y_data)

# Compare multiple strategies

print("\nComparing multiple fitting methods:")

methods_to_compare = ['linear', 'quadratic', 'exponential', 'power', 'ridge']

comparison_results = fitter.compare_methods(methods_to_compare)

for method_name, r_squared in comparison_results.items():

print(f"{method_name:15s}: R² = {r_squared:.3f}")

# Try a single method - pass string and plot it

result = fitter.fit('quadratic')

fitter.plot()

print(f"R² = {result['r_squared']:.3f}")

Problems with This Design

Every time you want to add a new fitting method, you must:

- Modify the

fit()method - add anotherelifbranch - Modify the

predict()method - add corresponding prediction logic - Risk breaking existing methods - any change could introduce bugs

- Re-test everything - you can’t be sure you didn’t break something

- Deal with growing complexity - the methods get longer and harder to understand

- Struggle with state management - some methods (like ridge) can’t even be implemented correctly because the design doesn’t maintain necessary state

The code becomes increasingly fragile. What if you typo 'linear' as 'liner' somewhere? What if the new method needs different return values? Each addition increases the risk of breaking validated code.

And did you notice the bug in ridge prediction?

elif self.method == 'ridge':

# ...

raise NotImplementedError("Ridge prediction not available after fitting")

The original design can’t even implement ridge prediction correctly because it doesn’t maintain the necessary state. This is a design failure that OCP prevents—each strategy naturally encapsulates its own state.

The Solution: Open/Closed Principle

This solves the validation nightmare: when you add a new fitting method, existing methods remain unchanged and don’t require re-validation.

Let’s refactor this using OCP. The key insight: Define an interface for fitting, then create separate classes for each method.

BEFORE: AFTER:

┌──────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐

│ DataFitter │ │ FitStrategy │ (abstract)

│ │ └─────────────┘

│ fit(): │ ↑

│ if linear │ (implements)

│ elif quad │ ┌─────────────┼─────────────┐

│ elif exp │ │ │ │

│ elif power │ ┌────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────────┐

│ elif ridge │ │ Linear │ │Quadratic│ │ Exponential │

│ │ └────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────────┘

│ predict(): │

│ if linear │ ┌───────────────┐

│ elif quad │ │ DataFitter │ (uses implementations)

│ elif exp │ │ (orchestrator)│

│ ... │ └───────────────┘

└──────────────┘

import numpy as np

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit

from scipy.stats import linregress

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

# ABSTRACTION: What all fitting methods must provide

class FitStrategy(ABC):

"""Abstract base class for fitting strategies."""

@abstractmethod

def fit(self, x_data, y_data):

"""Fit the model and return params and r_squared."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def predict(self, params, x_new):

"""Predict using the fitted params."""

pass

@property

@abstractmethod

def name(self):

"""Return the name of the strategy."""

pass

# CONCRETE IMPLEMENTATIONS: Each method in its own class

class LinearFit(FitStrategy):

"""Linear regression fitting strategy."""

def fit(self, x_data, y_data):

slope, intercept, r_value, _, _ = linregress(x_data, y_data)

return {'params': [intercept, slope], 'r_squared': r_value**2}

def predict(self, params, x_new):

intercept, slope = params

return intercept + slope * x_new

@property

def name(self):

return 'linear'

class QuadraticFit(FitStrategy):

"""Quadratic polynomial fitting strategy."""

def fit(self, x_data, y_data):

params = np.polyfit(x_data, y_data, 2)

predictions = np.polyval(params, x_data)

ss_res = np.sum((y_data - predictions)**2)

ss_tot = np.sum((y_data - np.mean(y_data))**2)

r_squared = 1 - (ss_res / ss_tot)

return {'params': params, 'r_squared': r_squared}

def predict(self, params, x_new):

return np.polyval(params, x_new)

@property

def name(self):

return 'quadratic'

class ExponentialFit(FitStrategy):

"""Exponential fit strategy: y = a * exp(b * x)."""

def fit(self, x_data, y_data):

def exp_func(x, a, b):

return a * np.exp(b * x)

params, _ = curve_fit(exp_func, x_data, y_data)

predictions = exp_func(x_data, *params)

ss_res = np.sum((y_data - predictions)**2)

ss_tot = np.sum((y_data - np.mean(y_data))**2)

r_squared = 1 - (ss_res / ss_tot)

return {'params': params, 'r_squared': r_squared}

def predict(self, params, x_new):

a, b = params

return a * np.exp(b * x_new)

@property

def name(self):

return 'exponential'

class PowerFit(FitStrategy):

"""Power law fit strategy: y = a * x^b."""

def fit(self, x_data, y_data):

log_x = np.log(x_data)

log_y = np.log(y_data)

slope, intercept, r_value, _, _ = linregress(log_x, log_y)

a = np.exp(intercept)

b = slope

return {'params': [a, b], 'r_squared': r_value**2}

def predict(self, params, x_new):

a, b = params

return a * x_new**b

@property

def name(self):

return 'power'

class RidgeFit(FitStrategy):

"""Ridge regression fitting strategy."""

def __init__(self, degree=3, alpha=1.0):

self.degree = degree

self.alpha = alpha

self.poly = None

self.ridge = None

def fit(self, x_data, y_data):

self.poly = PolynomialFeatures(degree=self.degree)

X_poly = self.poly.fit_transform(x_data.reshape(-1, 1))

self.ridge = Ridge(alpha=self.alpha)

self.ridge.fit(X_poly, y_data)

predictions = self.ridge.predict(X_poly)

ss_res = np.sum((y_data - predictions)**2)

ss_tot = np.sum((y_data - np.mean(y_data))**2)

r_squared = 1 - (ss_res / ss_tot)

return {'params': self.ridge.coef_, 'r_squared': r_squared}

def predict(self, params, x_new):

X_poly = self.poly.fit_transform(x_new.reshape(-1, 1))

return self.ridge.predict(X_poly)

@property

def name(self):

return 'ridge'

# ORCHESTRATOR: Uses fitting methods without knowing their details

class DataFitter:

"""Fits data using various methods following Open/Closed Principle."""

def __init__(self, x_data, y_data):

self.x_data = np.array(x_data)

self.y_data = np.array(y_data)

self.fit_result = None

self.strategy = None

def fit(self, strategy):

"""Fit data using the provided strategy object."""

self.strategy = strategy

self.fit_result = strategy.fit(self.x_data, self.y_data)

self.fit_result['method'] = strategy.name

return self.fit_result

def predict(self, x_new):

"""Make predictions using the fitted model."""

if self.strategy is None:

raise ValueError("Must fit model first")

x_new = np.array(x_new)

return self.strategy.predict(self.fit_result['params'], x_new)

def get_residuals(self):

"""Calculate fit residuals."""

predictions = self.predict(self.x_data)

return self.y_data - predictions

def plot(self, title=None):

"""Plot the original data and fitted curve."""

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create a dense x range for smooth curve

x_smooth = np.linspace(self.x_data.min(), self.x_data.max(), 100)

y_smooth = self.predict(x_smooth)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.scatter(self.x_data, self.y_data, label='Data', s=50, alpha=0.7)

plt.plot(x_smooth, y_smooth, 'r-', label=f'{self.strategy.name.capitalize()} fit', linewidth=2)

plt.xlabel('X')

plt.ylabel('Y')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.title(title or f'{self.strategy.name.capitalize()} Fit (R² = {self.fit_result["r_squared"]:.3f})')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

def compare_methods(self, strategies):

"""Compare multiple fitting strategies and return their R² values."""

results = {}

for strategy in strategies:

fit_result = strategy.fit(self.x_data, self.y_data)

results[strategy.name] = fit_result['r_squared']

return results

# USAGE: clean and extensible!

x_data = np.array([-3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6])

y_data = np.array([9.2, 6.1, 3.7, 2.0, 1.6, 1.8, 3.8, 6.0, 9.7, 13.5])

fitter = DataFitter(x_data, y_data)

# Compare multiple strategies easily

print("\nComparing multiple fitting methods:")

strategies = [LinearFit(), QuadraticFit(), ExponentialFit(), PowerFit(), RidgeFit()]

comparison_results = fitter.compare_methods(strategies)

for method_name, r_squared in comparison_results.items():

print(f"{method_name:15s}: R² = {r_squared:.3f}")

# Try a single method - pass strategy object and plot it

result = fitter.fit(QuadraticFit())

fitter.plot()

print(f"R² = {result['r_squared']:.3f}")

Why This Is Better

1. Easy to Extend

Want to add a new fitting method? Just create a new class:

class LogarithmicFit(FitStrategy):

"""Logarithmic fit strategy: y = a + b * ln(x)."""

def fit(self, x_data, y_data):

# Transform: y = a + b * ln(x)

# Fit as: y = a + b * x_log, where x_log = ln(x)

log_x = np.log(x_data)

slope, intercept, r_value, _, _ = linregress(log_x, y_data)

# slope is 'b', intercept is 'a'

return {'params': [intercept, slope], 'r_squared': r_value**2}

def predict(self, params, x_new):

a, b = params

return a + b * np.log(x_new)

@property

def name(self):

return 'logarithmic'

# Use it immediately without changing any existing code!

fitter = DataFitter(x_data, y_data)

result = fitter.fit(LogarithmicFit())

No modification to:

DataFitterclass- Any existing fitting methods

- Any existing tests

- Any validated code

2. Isolated Testing

When you add LogarithmicFit, you don’t need to re-run the tests for ExponentialFit. Why? Because ExponentialFit wasn’t modified—its code is identical to the validated version.

Each strategy can be tested independently:

import unittest

class TestExponentialFit(unittest.TestCase):

def test_perfect_exponential_data(self):

"""Test with data that perfectly follows exponential curve."""

x = np.linspace(0, 5, 50)

y_true = 2.0 * np.exp(0.5 * x)

strategy = ExponentialFit()

result = strategy.fit(x, y_true)

# Should fit nearly perfectly

self.assertGreater(result['r_squared'], 0.99)

# Parameters should be close to true values

a, b = result['params']

self.assertAlmostEqual(a, 2.0, places=1)

self.assertAlmostEqual(b, 0.5, places=1)

class TestLogarithmicFit(unittest.TestCase):

def test_new_method(self):

"""Test the new logarithmic fit thoroughly."""

# Extensive tests for the new method

# Old tests never need to run!

pass

In the if-elif version, every addition modifies the central fit() method, requiring full re-validation of all methods.

3. Type safety and IDE Support

Before:

fitter.fit('liner') # Typo! Runtime error

After:

fitter.fit(LinearFit()) # IDE catches if LinearFit doesn't exist

4. Protects Validated Code

Remember the validation nightmare from the opening? With OCP, when you add LogarithmicFit:

- ✅

LinearFitcode: unchanged → validation still valid - ✅

QuadraticFitcode: unchanged → validation still valid - ✅

ExponentialFitcode: unchanged → validation still valid - ✅ Your published results: safe

You only need to validate the new method. Your advisor can approve the addition without requiring full re-validation of the entire pipeline.

Red Flags that you need OCP

Ask yourself: “Can I add a new variant without modifying existing files?” If the answer is no, watch for these warning signs:

- Long if-elif or switch statements (>3 branches)

- Adding a variant requires editing multiple locations

- Similar code duplicated across branches

- String-based method selection (’linear’, ‘quadratic’, etc.)

- Tests that must re-run everything after any change

- Validated code that you’re afraid to touch

- Methods that can’t be fully implemented (like the ridge bug)

Common Mistakes: When Not to Use OCP

Don’t create this structure for:

❌ Simple, stable code:

# Don't need OCP for basic statistics

def calculate_stats(data):

return {

'mean': np.mean(data),

'std': np.std(data),

'median': np.median(data)

}

# This is stable, simple, and unlikely to expand

❌ Code you’ll use once:

# Exploratory analysis - keep it simple!

if method == 'a':

result = approach_a()

elif method == 'b':

result = approach_b()

# Throwaway code doesn't need robust architecture

✅ Do use OCP when:

- You expect to add new algorithms/methods regularly

- The code is validated and shouldn’t be modified

- Multiple people work on the same codebase

- Users need to provide their own implementations

- Different methods need different configuration

Performance Notes

Creating strategy objects has negligible overhead compared to the actual fitting computations. The real cost is in curve_fit(), polyfit(), and statistical calculations, not object instantiation.

Your Turn

- Find a place in your code with a long if-elif chain

- Identify what varies between the branches

- Create an abstract interface for that variation

- Extract one branch into a class

- Test that it works

- Extract the remaining branches one at a time

In the next post, we’ll explore the Liskov Substitution Principle: ensuring that your extended classes can truly substitute for their base classes without breaking things.

Have you been bitten by modifying validated code? Share your experiences in the comments!

Previous posts in this series:

Next in this series:

- Liskov Substitution Principle for Scientists - Coming next week

Meyer, Bertrand, Object-Oriented Software Construction (paid link). Prentice Hall, 1988. ↩︎